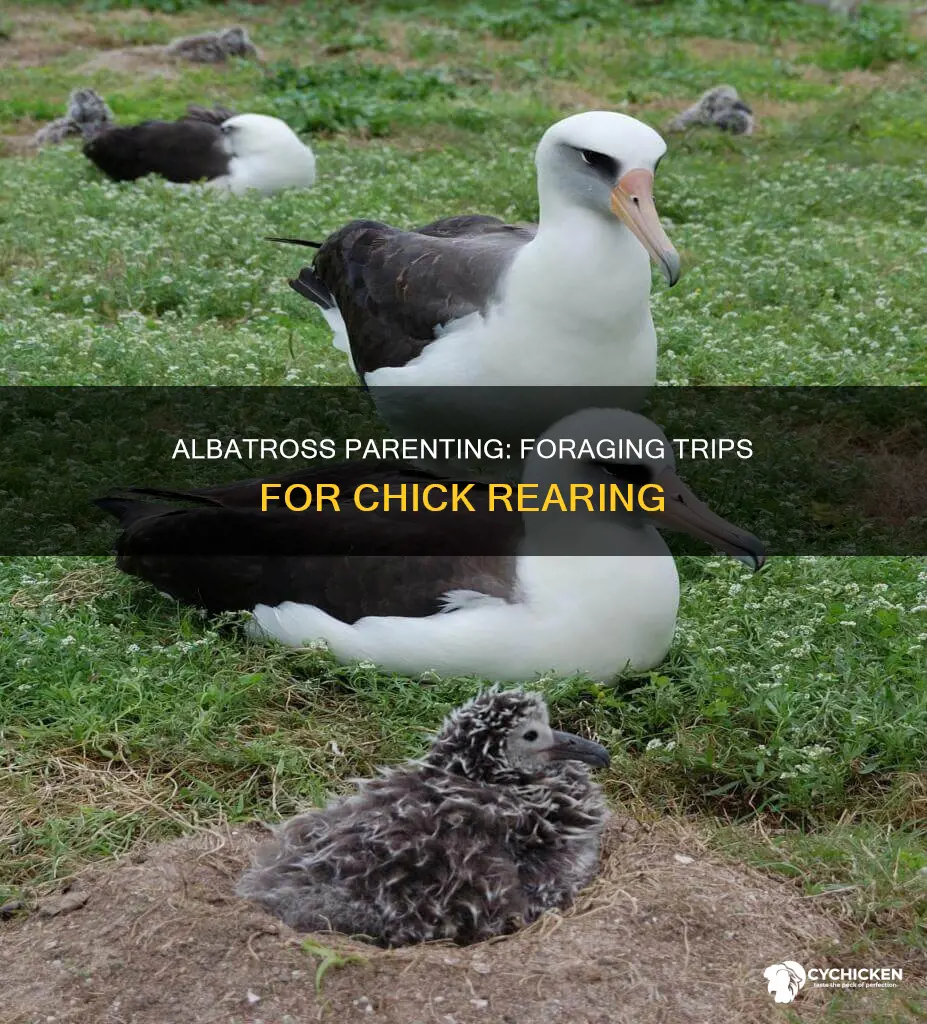

Albatrosses are well-adapted for long-distance travel, with their efficient mode of flight and anatomy that enables them to soar and glide with ease. This makes them excellent foragers, capable of covering vast distances with minimal energy expenditure. During the chick-rearing period, albatrosses employ different strategies, alternating between short and long foraging trips to balance food delivery to their chicks and restoring their body condition. The number of foraging trips can vary, with some species making frequent short trips, while others undertake fewer but longer journeys. The distance and duration of these trips are influenced by factors such as the age and size of the chicks, the availability of food sources, and the specific species of albatross.

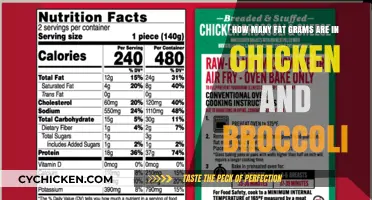

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Frequency of trips | Daily for the first two weeks, then less frequent as the parents forage farther at sea |

| Average trip duration | 2.5 days |

| Maximum trip duration | 17 days |

| Maximum distance travelled | 3,000 miles (Laysan Albatross) |

| Average meal weight | 12% of the adult albatross's body weight (around 600 g, or 21 oz) |

| Diet | Cephalopods (e.g. squid), fish, crustaceans, offal (organ meat), carrion, zooplankton, krill, fish eggs, floating carrion, discards from fishing boats |

What You'll Learn

- Albatrosses take shorter foraging trips during the brooding period

- Albatrosses may employ a dual foraging strategy when rearing larger chicks

- Albatrosses are well-adapted to long-distance travel

- Albatrosses combine soaring techniques with predictable weather systems

- Albatrosses use separate foraging zones during the breeding season

Albatrosses take shorter foraging trips during the brooding period

Albatrosses are well-adapted for long-distance travel, with their efficient mode of flight and anatomical specialization for soaring and gliding. They can cover great distances with minimal energy expenditure. However, during the brooding period, when chicks are young and require frequent meals, albatrosses take shorter foraging trips. This is a critical time for energy management, as adults need to maximize food delivery to their chicks while also maintaining their own body condition.

During the brooding period, albatrosses are limited to short-distance trips to ensure they can provide regular meals to their chicks. The foraging range contracts towards the end of the incubation period and becomes most restricted during brooding. This is when the chicks are still small and need to be fed frequently. As a result, adults alternate short trips with time spent at the nest, provisioning their young.

The number and duration of foraging trips during the chick-rearing period vary depending on the albatross species and the size of the chick. For example, Laysan and black-footed albatrosses breeding in the Hawaiian Islands have been recorded taking shorter trips during the brooding period, restricted to warm, oligotrophic waters. In contrast, yellow-nosed albatrosses have access to cooler, more productive waters, similar to their habitats during incubation and chick-rearing.

The light-mantled sooty albatross (LMSA) exhibits different behaviours during chick-rearing. While they generally follow diverse foraging routes, during chick-rearing, they may take shorter trips to the shelf and shelf-slope areas along the southern Scotia Arc or the mid-Scotia Sea. However, LMSA appears to have little capacity to regulate provisioning according to chick condition, and chick growth rates are slower compared to other albatross species.

Overall, while albatrosses are renowned for their long-distance travel capabilities, they adapt their behaviour during the brooding period by taking shorter foraging trips to ensure they can provide sufficient food for their growing chicks. This strategy helps them balance their energy needs with the demands of chick-rearing, maximizing the chances of survival and successful fledging.

Keep Chicken Nest Boxes Clean After Hatching

You may want to see also

Albatrosses may employ a dual foraging strategy when rearing larger chicks

Albatrosses are well-adapted to long-distance travel due to their economical mode of flight and anatomical specialization for soaring and gliding. These adaptations enable them to cover vast distances with minimal energy expenditure. During the incubation period, adult albatrosses can alternate between long shifts at the nest and far-ranging trips to sea.

As the chick-rearing period approaches, the foraging range of albatrosses contracts. This is because growing chicks require frequent meals, prompting adults to alternate between short trips to sea and time spent at the nest provisioning their offspring. When rearing larger chicks, albatrosses may employ a dual foraging strategy to balance their own needs with those of their chicks.

This strategy involves adults maximizing prey delivery to chicks by making short-distance trips and then restoring their energy reserves through long-distance foraging excursions. By optimizing their foraging behavior, albatross parents can ensure they have sufficient resources to support the growth and development of their chicks.

During the brooding period, albatrosses are typically restricted to short-distance trips to maximize food delivery to their chicks. Laysan and black-footed albatrosses, for example, are limited to foraging in warm, oligotrophic waters, where prey abundance may be lower. In contrast, yellow-nosed albatrosses have access to cooler, more productive waters, similar to those utilized during incubation and chick-rearing.

The ability to employ dual foraging strategies is a critical adaptation for albatrosses, enabling them to balance their energy needs with the demands of chick-rearing. By coordinating their foraging trips, albatross parents ensure consistent provisioning and minimize the risk of their chicks being abandoned for extended periods.

Chicken Houses: Counting America's Egg-Laying Abodes

You may want to see also

Albatrosses are well-adapted to long-distance travel

Albatrosses possess impressive flight dynamics and anatomical specializations for soaring and gliding, with long, slender wings that can span up to twelve feet. This allows them to glide efficiently across the water's surface, utilizing techniques like dynamic soaring to ascend into the wind and gain height, and then diving back down to gather speed. Their exceptional eyesight also aids in spotting food from great distances.

The lengthy "chickhood" of albatrosses is an adaptation to their patchy food supply. Slow-maturing chicks need food less often, allowing parents to forage for food over long distances. Albatross parents take turns incubating the egg and foraging for food, with one parent staying with the chick constantly for the first three to four weeks. As the chick grows, the parents stay away for longer periods to gather food, averaging about 2.5 days per visit but sometimes extending up to 17 days.

Albatrosses are known to have long life spans, with some living well beyond 50 years. They form strong, long-lasting pair bonds, and both parents participate equally in incubating the egg and feeding the chick. Albatrosses typically breed on remote islands and spend most of their time gliding over the open ocean. Their ability to predict the weather may also aid in their long-distance travel, as they can adjust their direction based on upcoming weather systems.

Chicken Cantina Bowl: Taco Bell's Carb Conundrum

You may want to see also

Albatrosses combine soaring techniques with predictable weather systems

Albatrosses are well-adapted for long-distance travel, with their economical mode of flight and anatomical specialization for soaring and gliding. They can cover vast distances with minimal effort, thanks to their ability to harness the wind effectively. This is achieved through dynamic soaring, where albatrosses and other large seabirds use wind energy to travel long distances swiftly and with little apparent exertion.

During the incubation period, adult albatrosses can take turns incubating the egg while the other ventures out on extended foraging trips. As the end of incubation approaches, their foraging range contracts, and during the brooding period, when chicks require more frequent meals, the foraging range becomes even more restricted. This is when the chicks are fed every day for the first two weeks, after which feedings become less frequent as the parents venture farther.

Albatrosses, particularly the wandering albatross, combine their dynamic soaring techniques with predictable weather systems to cover large distances efficiently. By utilizing looping flight patterns, they can maximize their chances of encountering favorable winds. When heading north, they fly in anticlockwise loops, while their movements in the south follow a clockwise direction. This strategic utilization of weather systems allows albatrosses to travel extensively with minimal energy expenditure, making them well-suited for their demanding chick-rearing responsibilities.

The Laysan Albatross, for example, may travel up to 3,000 miles round trip to gather food for their chicks. They feed their chicks stomach oil, which is produced by digesting food in their stomachs. Albatrosses also have a unique adaptation, a salt gland that excretes excess salt, allowing them to drink seawater without dehydration. This adaptation, along with their soaring techniques and understanding of weather systems, equips them to be efficient foragers and caregivers for their chicks.

Build a Chicken Watering System: Nipple Setup Guide

You may want to see also

Albatrosses use separate foraging zones during the breeding season

Albatrosses are large-sized marine predators with a wide range and the ability to travel long distances. They are well-adapted to long-distance travel due to their economical mode of flight and anatomical specialization for soaring and gliding. Their ability to use wind to reduce flight costs and spend more time in the air at night makes them well-suited for exploiting distant foraging grounds.

During the breeding season, albatrosses invest in central-place foraging, making long-range movements to access similar marine habitats. For example, Laysan and black-footed albatrosses breeding in the Hawaiian Islands and Indian yellow-nosed albatrosses breeding in the southern Indian Ocean utilize marine habitats in two different ocean basins. These albatrosses take longer foraging trips during incubation compared to brooding, and they utilize subtropical-subpolar transition zones where warm and cool waters meet, providing enhanced foraging opportunities.

The foraging range of albatrosses is constrained during the breeding period due to changing energy requirements at the nest. During incubation, breeding pairs can alternate long shifts at the nest with far-ranging trips, but as the chick-rearing period approaches, one parent stays with the chick constantly for the first three to four weeks, and the foraging range becomes more restricted. As the chick grows, the parents take longer trips to restore their body condition and maximize prey delivery.

Interestingly, male and female albatrosses may use separate foraging zones during the breeding season. Males progressively move from subtropical waters to Antarctic waters as they mature, while females remain in subtropical waters throughout their lives but increase their travel speed with age. This difference in foraging zones between the sexes may be related to the different physical demands of breeding and rearing chicks.

In summary, albatrosses exhibit dynamic and adaptive foraging strategies during the breeding season, utilizing various marine habitats and adjusting their trip durations and ranges based on the stage of chick development. The use of separate foraging zones by males and females further highlights the complexity and flexibility of albatross foraging behavior.

Chicken Crusts: Carb Counts for Caesar and Parmesan Varieties

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Albatross parents adopt alternative patterns of short and long foraging trips, providing meals that weigh around 12% of their body weight. During the brooding period, when young chicks require frequent meals, adults alternate short trips to the sea with time spent at the nest.

Albatross chicks are fed every day for the first two weeks of life. After that, feedings get less frequent as the parents forage farther at sea. They average about 2.5 days per visit, but sometimes they only stay long enough to feed.

Albatrosses are well-adapted to long-distance travel. The farthest-known single foraging one-way trip for a Laysan albatross feeding its chick was 1,600 miles, which is more than 3,000 miles round trip. Laysan albatrosses may travel up to 3,000 miles to gather food for their chicks.